Benjamin Banneker

Benjamin BannekerBenjamin Banneker was a free African American astronomer, mathematician, surveyor, almanac author and farmer. Although it is difficult to verify details of Benjamin Banneker's family history, it appears that he was a grandson of a European American named Molly Welsh. The story goes that Molly met a slave named Banneka when she purchased him to help establish a farm located near the future site of Ellicott's Mills, west of Baltimore, Maryland. This part of Maryland was out of the mainstream of the colonial South, and as result had a more tolerant attitude toward African Americans than did colonial areas in which slavery was more prevalent.

Perhaps a member of the Dogon tribe (reputed to have a historical knowledge of astronomy), Banneka may have cleared Molly's land, solved irrigation problems, and implemented a crop rotation for her. Soon thereafter, Molly freed and married Banneka, who may have shared his knowledge of astronomy with her. Benjamin's mother, Mary, was the daughter of Molly and Banneka.

Although born after Banneka's death, Benjamin may have acquired some of his grandfather's knowledge via Molly, who appears to have taught him how to read, farm, and interpret the sky as Banneka had taught her. Little is known about Benjamin's father Robert, a first-generation slave who had fled his owner.

As a young teenager, Banneker met and befriended Peter Heinrichs, a Quaker farmer who established a school near Banneker's family's farm. Heinrichs shared his personal library with Banneker and provided Banneker's only classroom instruction. (During Banneker's lifetime, Quakers were leaders in the antislavery movement and advocates of racial equality in accordance with their Testimony of Equality belief.)

Apparently using as a model a pocket watch that he had borrowed from a merchant or traveller, Banneker carved wooden replicas of each piece and used the parts to make a clock that struck hourly. He completed the clock in 1753, at the age of 21. The clock continued to work until his death.

Apparently using as a model a pocket watch that he had borrowed from a merchant or traveller, Banneker carved wooden replicas of each piece and used the parts to make a clock that struck hourly. He completed the clock in 1753, at the age of 21. The clock continued to work until his death.Then in 1771, a white Quaker family, the Ellicotts, moved into the area and built mills along the Patapsco River. Banneker supplied their workers with food, and studied the mills.

In 1788 he began his more formal study of astronomy as an adult, using books and equipment that George Ellicott lent to him. The following year, he sent George Ellicott his work on the solar eclipse. In February 1791, Major Andrew Ellicott, a member of the same family, hired Banneker to assist in a survey of the boundaries of the 100-square-mile (260 km2) federal district (initially, the Territory of Columbia; later, the District of Columbia) that Maryland and Virginia would cede to the federal government of the United States for the nation's capital in accordance with the federal Residence Act of 1790 and later legislation. Banneker's activities on the survey team resembled those used in celestial navigation during his lifetime. His duties consisted primarily of making astronomical observations at Jones Point in Alexandria, Virginia, to ascertain the location of the starting point for the survey and of maintaining a clock that he used when relating points on the surface of the Earth to the positions of stars at specific times.

Because of illness and the difficulties in helping to survey the area at the age of 59, Banneker left the boundary survey in April 1791 and returned to his home at Ellicott's Mills to work on an ephemeris. At Ellicott's Mills, Banneker made astronomical calculations that predicted solar and lunar eclipses for inclusion in his ephemeris. He placed the ephemeris and its subsequent revisions in a six-year series of almanacs, which were published for the years 1792 through 1797 in Baltimore and Philadelphia. He also kept a series of journals that contained his notebooks for astronomical observations, his diary, and his mathematical calculations. The title page of Banneker's 1792 Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland and Virginia Almanack and Ephemeris stated that the publication contained:

the Motions of the Sun and Moon, the True Places and Aspects of the Planets, the Rising and Setting of the Sun, Place and Age of the Moon, &c.—The Lunations, Conjunctions, Eclipses, Judgment of the Weather, Festivals, and other remarkable Days; Days for holding the Supreme and Circuit Courts of the United States, as also the useful Courts in Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia. Also—several useful Tables, and valuable Receipts.—Various Selections from the Commonplace–Book of the Kentucky Philosopher, an American Sage; with interesting and entertaining Essays, in Prose and Verse—the whole comprising a greater, more pleasing, and useful Variety than any Work of the Kind and Price in North America.

Supported by Andrew, George and Elias Ellicott and heavily promoted by the Society for the Promotion of the Abolition of Slavery of Maryland and of Pennsylvania, the early editions of the almanacs achieved commercial success. After these editions were published, William Wilberforce and other prominent abolitionists praised Banneker and his works in the House of Commons of Great Britain. Banneker expressed his views on slavery and racial equality in a letter to Thomas Jefferson and in other documents that he placed within his 1793 almanac. The almanac contained copies of his correspondence with Jefferson, poetry by the African American poet Phillis Wheatley and by the English anti-slavery poet William Cowper, and anti-slavery speeches and essays from England and America.

On February 15, 1980, the United States Postal Service issued in Annapolis, Maryland, a 15 cent stamp that illustrated a portrait of Banneker. An image of Banneker standing behind a short telescope mounted on a tripod is superimposed upon the portrait. The device shown in the stamp resembles Andrew Ellicott's transit and equal altitude instrument, which is presently in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. The stamp is part of the Postal Service's Black Heritage stamp series.

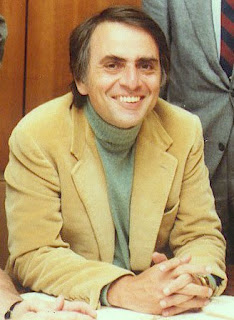

Carl Sagan

Carl Edward Sagan (1934-1996) was an American astronomer, astrochemist, author, and highly successful popularizer of astronomy, astrophysics and other natural sciences. He pioneered exobiology and promoted the Search for Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence (SETI).

He is world-famous for writing popular science books and for co-writing and presenting the award-winning 1980 television series Cosmos: A Personal Voyage, which has been seen by more than 500 million people in over 60 countries. A book to accompany the program was also published. He also wrote the novel Contact, the basis for the 1997 film of the same name. One of the last books he wrote was Pale Blue Dot. During his lifetime, Sagan published more than 600 scientific papers and popular articles and was author, co-author, or editor of more than 20 books. In his works, he frequently advocated skeptical inquiry, secular humanism, and the scientific method.

He attended the University of Chicago, where he participated in the Ryerson Astronomical Society, received a B.A. with general and special honors (1954), a B.S. (1955) and a M.S. (1956) in physics, before earning a Ph.D. degree (1960) in astronomy and astrophysics. During his time as an undergraduate, Sagan spent some time working in the laboratory of the geneticist H. J. Muller. From 1960 to 1962 he was a Miller Fellow at the University of California, Berkeley.

From 1962 to 1968, Sagan worked at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Sagan lectured and did research annually at Harvard University until 1968, when he moved to Cornell University in New York. He became a full Professor at Cornell in 1971, and he directed the Laboratory for Planetary Studies there. From 1972 to 1981, Sagan was the Associate Director of the Center for Radio Physics and Space Research at Cornell.

Sagan was a scientist connected with the American space program since its inception. From the 1950s onward, he worked as an adviser to NASA. One of his many duties during his tenure at the space agency included briefing the Apollo astronauts before their flights to the Moon. Sagan contributed to many of the robotic spacecraft missions that explored the solar system during his lifetime, arranging experiments on many of the expeditions. He conceived the idea of adding an unalterable and universal message on spacecraft destined to leave the solar system that could potentially be understood by any extraterrestrial intelligence that might find it. Sagan assembled the first physical message that was sent into space: a gold-anodized plaque, attached to the space probe Pioneer 10, launched in 1972. Pioneer 11, also carrying another copy of the plaque, was launched the following year. He continued to refine his designs throughout his lifetime; the most elaborate message he helped to develop and assemble was the Voyager Golden Record that was sent out with the Voyager space probes in 1977. Sagan often challenged the decisions to fund the Space Shuttle and Space Station at the expense of further robotic missions.

At Cornell University, Sagan taught a course on critical thinking until his death in 1996 from a rare bone marrow disease. The course had only a limited number of seats. Although hundreds of students applied each year, only about 20 were chosen to attend each semester. The course was discontinued immediately after Sagan's death, but it was resumed by Dr. Yervant Terzian in 2000.

Sagan's contributions were central to the discovery of the high surface temperatures of the planet Venus. In the early 1960s no one knew for certain the basic conditions of that planet's surface, and Sagan listed the possibilities in a report later depicted for popularization in a Time-Life book, Planets. His own view was that Venus was dry and very hot as opposed to the balmy paradise others had imagined. He had investigated radio emissions from Venus and concluded that there was a surface temperature of 500 °C (900 °F). As a visiting scientist to NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, he contributed to the first Mariner missions to Venus, working on the design and management of the project. Mariner 2 confirmed his conclusions on the surface conditions of Venus in 1962.

Sagan was among the first to hypothesize that Saturn's moon Titan might possess oceans of liquid compounds on its surface and that Jupiter's moon Europa might possess subsurface oceans of water. This would make Europa potentially habitable for life. Europa's subsurface ocean of water was later indirectly confirmed by the spacecraft Galileo. Sagan also helped solve the mystery of the reddish haze seen on Titan, revealing that it is composed of complex organic molecules constantly raining down onto the moon's surface.

He further contributed insights regarding the atmospheres of Venus and Jupiter as well as seasonal changes on Mars. Sagan established that the atmosphere of Venus is extremely hot and dense with pressures increasing steadily all the way down to the surface. He also perceived global warming as a growing, man-made danger and likened it to the natural development of Venus into a hot, life-hostile planet through a kind of runaway greenhouse effect. Sagan and his Cornell colleague Edwin Ernest Salpeter speculated about life in Jupiter's clouds, given the planet's dense atmospheric composition rich in organic molecules. He studied the observed color variations on Mars’ surface and concluded that they were not seasonal or vegetational changes as most believed but shifts in surface dust caused by windstorms.

He is also the 1994 recipient of the Public Welfare Medal, the highest award of the National Academy of Sciences for "distinguished contributions in the application of science to the public welfare."

Sagan is best known, however, for his research on the possibilities of extraterrestrial life, including experimental demonstration of the production of amino acids from basic chemicals by radiation. Sagan was a proponent of the search for extraterrestrial life. He urged the scientific community to listen with radio telescopes for signals from intelligent extraterrestrial life-forms. So persuasive was he that by 1982 he was able to get a petition advocating SETI published in the journal Science and signed by 70 scientists including seven Nobel Prize winners. This was a tremendous turnaround in the respectability of this controversial field. Sagan also helped Dr. Frank Drake write the Arecibo message, a radio message beamed into space from the Arecibo radio telescope on November 16, 1974, aimed at informing extraterrestrials about Earth.

Sagan was chief technology officer of the professional planetary research journal Icarus for twelve years. He co-founded the Planetary Society, the largest space-interest group in the world, with over 100,000 members in more than 149 countries, and was a member of the SETI Institute Board of Trustees. Sagan served as Chairman of the Division for Planetary Science of the American Astronomical Society, as President of the Planetology Section of the American Geophysical Union, and as Chairman of the Astronomy Section of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Sagan believed that the Drake equation, on substitution of reasonable estimates, suggested that a large number of extraterrestrial civilizations would form, but that the lack of evidence of such civilizations highlighted by the Fermi paradox suggests technological civilizations tend to destroy themselves rather quickly. This stimulated his interest in identifying and publicizing ways that humanity could destroy itself, with the hope of avoiding such a cataclysm and eventually becoming a spacefaring species.

Sagan was skeptical of reports of UFO. He thought scientists and investigators should examine them to address the widespread public interest in UFO reports. In 1964, he had several conversations on the subject with Jacques Vallee.

Stuart Appelle notes that Sagan "wrote frequently on what he perceived as the logical and empirical fallacies regarding UFOs and the abduction experience. Sagan rejected an extraterrestrial explanation for the phenomenon but felt there were both empirical and pedagogical benefits for examining UFO reports and that the subject was, therefore, a legitimate topic of study.

Editors Note: Truly an inspiration to those of us who look at the world as part of the universe and not the center of the universe. There is so much to write and discuss on such a phenomenal person who is a personal hero of my husband and I, that we don’t have enough space for it all. Thank you, Carl, for asking the primary questions: How and Why?

For further reading:

http://www.carlsagan.com/

www.stephenjaygould.org/ctrl/sagan_science.html

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Communication_with_Extraterrestrial_Intelligence

Truly a great man, so forward thinking. He is quoted as saying "It is far better to grasp the universe as it really is, than to persist in delusion, no matter how satisying and reassuring."

ReplyDeleteIf "N x fp x ne x fl x fi x fc x fL" equaled just "Carl Sagan", then it works for me...apologies for my deviation from syntax. A hero to many, including Pharrell of hip-hop fame. I carry this guy in my brain like a nerd carries a pocket book and pens. He's helped in many a drunken argument.

ReplyDeleteKudos on Benjamin Banneker too. I had never heard of him before now.

Great Post!